Let's start with some basic principles. In general, those lots which are easiest and cheapest to build on would be expected to be the most valuable. Approximately rectangular lots are easier and cheaper to build on than lots in irregular shapes, and within those constraints approximately square lots are easier and cheaper to build on than narrow and elongated ones.* We should therefore expect to see the residential areas of most cities composed of roughly square lots, and in fact this is exactly what can be witnessed in, for instance Japanese cities, with lots in the Tokyo development shown below of 32' x 38' (all images from Bing Maps):

To maintain a favorable ratio of private to public land, the roads in such a scenario must be quite narrow, as I mentioned in the previous post, and that is what is generally seen in Japanese cities.

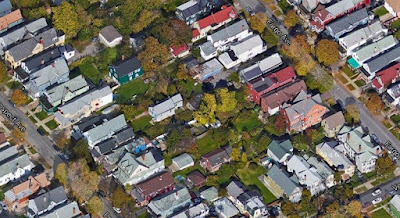

In American cities, by contrast, the common historical pattern has been both wide blocks and streets. In order to respond to high demand for housing, therefore, the solution has been to slice lots thinner and thinner. Although this does increase the number of lots per block, it adversely affects their utility, leaving the builder to construct a very long and narrow house. An example is from an older neighborhood in Buffalo, NY -- a neighborhood more than a century older than the one above -- with lots of 30' x 175':

Why, it could be asked, were these blocks made so wide? What sort of development was anticipated? Why were the blocks not subdivided with additional streets, as famously happened in Philadelphia? Instead of any of these options, it appears most lots were densified vertically, through the construction of two and three-family wooden houses.

And yet, even were each lot built out as a three-story, three-unit home, the density would be less than in the Japanese example, and without one single-family detached house. Not all blocks in Buffalo are so wide, but few are much narrower.

For comparison, let's examine the blocks of Detroit, a city long known for its prevalence of single-family detached housing. Lots here (a neighborhood of the 1910s or 1920s) are 34' x 125', a more reasonable dimension that's helped the city maintain its high share of single-family housing. Note also the presence of alleys here through the center of the block.

As the development of American suburbs progressed during the 20th century, the width-to-depth ratio continued to moderate. Here, in Levittown, from circa 1950, lots are 60' x 110' with no alleys. The blocks are visibly narrower than in the Detroit example:

Finally, in some of the developments of the 1960s and 70s we see what are approximately square residential lots. Here, for example, is Herndon, VA, with lots of 90' x 105'. Interestingly, the ranch houses still "sprawl" across the wide lot, continuing to create the visual effect of a more or less solid wall of houses to a person going past:

Having the distance between the side walls of houses as a fraction of that between the fronts and backs of houses is a common feature of American residential developments in all eras, it seems.

There appears to have been a reversion to Levittown dimensions in the subdivisions of the 1990s and 2000s, with the New Urbanism even reintroducing deep narrow lots in the pre-1950 style in its more recent developments.

-------------------

I'd posed the question above of why the earliest lots were made to be so inefficiently long and narrow. Land values obviously compelled the narrow widths, but why had blocks been made so wide in the first place? Were the surveyors of the 19th century under the impression that American homeowners, like the villagers of Tsarist Russia or medieval western Europe, would be tending to "dacha"-style backyard gardens for sustenance?

Perhaps. John Reps, in his The Making of Urban America, confirms that some of the earliest planned settlements in North America intended individual house lots to be used for gardening purposes:

"If it can be tentatively concluded that the New Haven [Connecticut] plan, with its generous provision for open space, was no sudden inspiration of the moment, there is no ready explanation for the source of its form or dimensions. ... The large residential blocks did not long retain their original form. Intended to provide generous garden plots adjacent to residences, these deep squares were eventually divided into four smaller blocks by new streets running at right angles from the midpoints of their sides. . . ." The Making of Urban America: A History of City Planning in the United States, p. 130.Were the blocks of a city like Buffalo, laid out as early as 1804 by a man from rural Bucks County, Pennsylvania, similarly designed to provide an urban facsimile of the rural farmstead in what was then wilderness of Western New York? Whatever the reason, the blocks were poorly-suited to the industrializing city that emerged a few decades later. The legacy of these blocks with their very narrow lots was only gradually discarded over the next century or more.

---------------------

Rather than building very narrow multifamily structures on these narrow lots, which in general have not fared well in Buffalo and which have simply vanished from large swathes of the city (as have, to be fair, many of Detroit's single-family houses), what other options are available? There are a few related possibilities, assuming we limit ourselves to single-family structures. For example:

- As in New Haven and Philadelphia, build new streets into the blocks to create new, smaller blocks with more reasonable dimensions.

- Allow condominium development to stretch back from the street in rowhouse and/or detached form, which would allow numerous owner-occupied units on each lot.

- Where alleys exist, allow new houses (i.e. ADUs, accessory dwellings, "granny flats," etc.) to be built along them.

Where three lots once hosted perhaps three duplexes with two two bedroom units each (the Buffalo "2/2"), there are now eight fairly large (1800 sq. ft.) single-family homes, or, if homes were divided by floor, as many as sixteen one and two-bedroom units. A small lane (or really narrow street if you prefer) runs in between the homes, and cars can be parked alongside houses. The backyard is heavily truncated, but there is enough space for a small patio. If the above design were extended to another three lots on the opposite side of the block, the lane would become a small through-street, helping to open up the large blocks. Further, if the houses were made slightly smaller, I think it would be possible to fit in ten rather than eight. You can do the math.

This style is largely what Nathan Lewis has called "single-family detached in the traditional style." As an infill strategy, it is uncommon in the older cities of the Eastern US, but may have promise in circumstances like those in Buffalo where deep lots leave a large amount of unusable land. A condominium development would look much the same, similar to what can be seen here in Stamford, CT on similarly deep lots:

Houston, in particular, has countless examples of this sort of townhouse or compact single-family infill development, especially in and around the Montrose neighborhood. A Google maps tour of the area will reveal the various ways such developments can be planned and arranged.

The ADU approach is so well-known I need not provide any examples of it here, but it is obviously less practical in situations where there are no alleys, as in Buffalo, which if lots were to be legally separated would require either complex shared driveway arrangements or the use of flag lots, impractical where the lot is already so narrow.

There is much more that could be done with multifamily housing, but that will need to wait for another post.

*As Nathan Lewis has noted, long, elongated houses are inefficient users of resources, requiring more wall length per square foot than a square house. These dimensions are also less favorable for energy conservation, as there are more points for heat to escape.

Related posts:

Another important factor in lot dimensions is how property taxes were historically calculated. This is a potentially rich subject but one that's very difficult to research and as far as I know nobody has tackled it in any comprehensive way.

ReplyDeleteThe reason it's important is because, as far as I've been able to tell, historically in most US cities property taxes were levied on lot frontage. It's easy to calculate and administer, and it also encourages maximizing development because there's no tax penalty for building bigger. It does create an incentive to subdivide however, so that's another likely reason we see so many deep narrow lots.

I believe that in Charleston, SC they did things a little differently, charging based on building frontage rather than lot frontage. So the result there is sometimes comically narrow buildings with open porches and quite sumptuous side yard gardens. Yes there's also climate issues requiring better access to breezes, and being a mostly wood-framed city there's more reason to have detached housing compared to nearby Savannah which is more masonry and also more attached, suggesting the climate isn't actually a factor for attached vs. detached housing.

Great point, Jeffrey. I do wonder now how Buffalo calculated its property taxes during the 19th c. The very narrow lots do suggest that possibility. And I wonder whether it was legal then to have a lot without street frontage -- there seem to be virtually no separated rear lots the city, but there are a few instances of 30' lots chopped in half! Not built on, though, sadly. I think you're right that this is a very difficult subject to research, and I wouldn't even know where to start. I'll see if I can dig up anything.

DeleteWell, here is the Buffalo property tax list from 1912: https://books.google.com/books?id=-8REAQAAMAAJ&pg=RA1-PA166&lpg=RA1-PA166&dq=city+of+buffalo+property+tax+1890&source=bl&ots=thWazWdYZN&sig=tkNeIOGpBvbXLxgixfLjsX1wU4g&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiS__Cf4KLLAhWJ8j4KHW3LDSUQ6AEIMTAD#v=onepage&q=city%20of%20buffalo%20property%20tax%201890&f=false

DeleteAs best I can tell, it looks like taxes are being assessed on improvements + value of land as measured in square feet, but it's not entirely clear. I'll keep looking for earlier records. There is very little academic research on this except in very general terms.

I'm really surprised that you are unaware of why lots are long and narrow. That's just basic real estate: divide the land into the largest number of plots with each having access to the thoroughfare. Much like the way that the French parceled land along the Mississippi so that each plantation would have access to the river but the bulk of their land was behind it which allowed more lots to be sold as part of Mississippi Bubble: https://goo.gl/maps/G8tunCNFQxm

ReplyDeleteBLVD -- I understand the economic necessity behind narrowly-divided lots, as I wrote in the post, but was unsure why the blocks had been so wide to begin with. There should have been an incentive to create more thoroughfares for more saleable lots. An urban environment is somewhat different than selling farmland along the Mississippi from that perspective.

DeleteI think a good explanation for this is the streetcar. Longer blocks along the direction of travel made for fewer stops and faster transit time, and streetcar developers often laid out the new subdivisions for sale. Not all US cities, but many.

DeleteA good case study proving this out is Mpls/StP, where Minneapolis, with mostly north-south lines (at least, the non-inter-urban ones), has tall and skinny blocks. St Paul had streetcar lines running E-W, with identical block dimensions as Minneapolis but rotated 90 degrees.

Manhattan has wide and narrow blocks running across the island. I suspect this was to make transport of goods to/from ports on either river faster, with traveling long distances up or down the island a lesser concern when the Manhattan grid was planned. Someone can weigh in if this is true or not :).

Charlie, I get what you're saying but I don't think turn of the century developers cared about the perceived values square vs rectangular lots. They simply wanted to sell land that on paper had the most square feet per frontage. Regarding NYC, as I read, the blocks were laid out not facilitate transit but simply because that arrangement allowed for the maximum number of lots to sold. Do you think selling two 1500 sq feet lots would net more then one 5000 sq ft lot?

Delete@BLVD -- I don't know the answer to that. My assumption would be that two 2,600 sq ft lots would net more than one 5,200 sq ft lot, but that may not have been true at the time they were initially sold. Today, land values are so low that there's little incentive to subdivide, but that hopefully won't be the case forever.

Delete@Alex -- I think that's a great point. I'll have to locate Buffalo's old streetcar map. A lot would depend on exactly when the blocks were laid out. Here's an 1849 map for reference, showing that the block in question was already there at that time, probably laid out very recently (in the northwest portion): http://www.archivaria.com/GdDhistory/Buffalo1849.jpg

Canadian cities don't seem to have blocks laid out to maximize length parallel to streetcar routes... if anything it's the opposite.

DeleteLogically, it makes sense to have blocks laid out so that they're short along streetcar routes, from the point of view of developers. It means residents get a direct route to the streetcar line, which even if it doesn't stop at every intersection, is often lined with retail, so it will be a direct route to the retail strip.

One point of clarification from planner-world. The "width" of a lot is reserved for the distance along the street; "depth" is the preferred term for front to back. So, excessively deep lots, deep blocks, etc. Sounds weird, I know.

ReplyDeleteAs far as remedies for excessively deep lots, you've hit on most of them.

Your diagram shows shows what's sometimes called cottage housing, wherein two or more lots are combined for multiple single-family dwellings. Your example shows an even distribution across the site, but generally there is some clustering to allow for good site circulation and common open space.

Another useful technique is to allow for zero lot line development. Instead of maintaining narrow side yards on both sides of the house, simply slide the house over to one side of the lot and retain a wider, accessible side yard on the other. Generally, you need three or more lots for the shifting to work without complications, but it makes ADUs and deeper construction more feasible, and doesn't really disrupt the continuity of the block.

Thanks Anonymous planner! Have updated the terminology. My thought here was that each house would sit on its own lot, but a cottage housing approach could work, too.

DeleteHaving lots of a certain depth would still make sense if you want a yard though. If the yard is intended to be used for something rather than just a privacy buffer, it makes sense to have most of the yard space on one side of the house, a the most logical side to me is the back. The result would be a rectangular lot, maybe about twice as deep as it is wide.

ReplyDeleteWith row houses the lots would be even deeper relative width due to shared walls.

Perhaps the founders of Buffalo, and many other cities from that era just didn't expect densities to exceed narrow lot single family densities much. There were only a handful of American cities that had achieved higher densities by then and perhaps the founders thought these new cities would be different or remain smaller.

I think that's a very good point, Nick. The block that I show above appears on an 1849 map of the city. At the time, the population of was only around 40,000. However, most of the homes in that area weren't built until around 1900-1920, at which point land values had clearly risen dramatically and two/three family homes were built instead of single-family homes.

DeleteDo you have a feel for how many 2-3 family homes there were in the city as a whole?

DeleteBuffalo has also built backyard cottages in a few areas.

https://www.google.ca/maps/@42.8700411,-78.8488762,3a,75y,200.31h,89.18t/data=!3m7!1e1!3m5!1ss36abBpYtuhdT3qrHdvWbg!2e0!6s%2F%2Fgeo1.ggpht.com%2Fcbk%3Fpanoid%3Ds36abBpYtuhdT3qrHdvWbg%26output%3Dthumbnail%26cb_client%3Dmaps_sv.tactile.gps%26thumb%3D2%26w%3D203%26h%3D100%26yaw%3D308.66556%26pitch%3D0!7i13312!8i6656

Cleveland, which has a similar housing stock of turn of the century/early 20th century SFHs mixed with 2-3 family homes on deep lots, also has some backyard cottages in Asia Town.

Fredericton, NB also has some lots with rear additions to SFHs to convert them to multi-family. I think many small New England towns are similar.

All in all though, I think if you want a truly great variety of housing and building types within a neighbourhood, you also need a variety of block sizes and street widths.

While one can never discount the gentry fantasy working in American life -- I think you had a post a while back quoting a book from the 19th century whose author was puzzled by Americans' love for cottage housing -- I think there are a couple other explanations.

ReplyDelete1) American city leaders were insistent that developers conform to the plan. New York City, for example, once it adopted the Commissioners' Plan laying out its grid was extremely loth to allow any small streets to interrupt it, even when there was a need, the main exception being Central Park. Similarly, American cities in the 19th century refused to allow any street narrowing, despite the advantages it would have had.

2) It could be a conscious choice by the developer. Many housing developments of the streetcar era were built rather quickly, both because of high housing demand and to get people on the streetcar line as soon as possible, so they were less worried about using land efficiently because they were going to sell it quickly.

3) Rectangles were popular. The tract housing of England's industrialization was built on narrow, deep lots. Deep, narrow houses are also common in Boston, where there was some rear infill.

I also note that, in looking at Buffalo on Google Maps, it appears that there was rear, infill development. Blocks get wider and longer as one proceeds from the core. Closer to and in Downtown the blocks are smaller and more square. So the underutilization of land may just be a result of Buffalo's population leveling off in the 30s before falling off a cliff in the 50s.

I wonder if narrow but deep lots were a compromise to increase the number of destinations along the street front while still offering a lot of area.

ReplyDeleteYes. The interface between home and street only requires 1-2 car widths, a front door, and utility connections. The next layer is a psychological and symbolic connection to the public sphere, so we add a den with a window. Voila: the 36' wide cluster home, often on a culd-de-sac.

DeleteIt is possible that deep and narrow lots are simply the result of a trend towards having wider streets in the 19th century onward. A wide street is obviously more expensive than a narrow street and is a drag on public funds, so wider streets would create an incentive to have deeper, narrower lots so as to maintain the square footage of streets per lot roughly the same.

ReplyDeleteBTW, you might also want to look at financial incentives. In Europe, many countries had window taxes that levied taxes based on the number of windows of a house. In North America, some jurisdictions charged a frontage tax based on lot width at the curb. Both of these taxes may provide an incentive to favor narrow lots to reduce the tax burden (narrow lots limiting the number of windows you can have).

As to design, I think we should also always remember the resident's perspective and not just the urban explorer's. Deeper lots allow for deeper back yards and greater setbacks, the result of which is a greater distance from house to house, which increases light access per window and privacy while inside the house.

For example, a lot 40-meter deep can have a backyard 20-meter deep, a house 10-meter deep and a front yard 10-meter deep. If the street is also 10-meter deep, then that means that two houses that face each other will be 30 meters away from one another. Two houses back to back will be 40 meters away from one another, measuring back wall to back wall.

On the other hand, a shallow lot of 20 meters for example cannot have similarly deep yards. Supposing a house 8-meter deep, that leaves maybe 4 meters for the front yard and 8 meters for the back yard. Even if the street is still 10 meters wide, that means that houses that face each other are just 18 meters away, and houses back to back have just 16 meters away from each other. So, looking from the houses' window, other houses will likely *look* twice as wide and tall as on a street with deep lots, and privacy will be lessened.

The flip side is that a wide but shallow lot allows for more front and back windows than a deep but narrow lot.

It's a great post, but one thing that doesn't get mentioned is the tradeoff between public cost (infrastructure) to private cost (construction cost). When merely paving the the street is a monumental achievment, as it often was in the 19th century, there is an incentive to maximize the properties along it by making them deep and narrow. Even if a narrow house costs more to build the tradeoff is worth it. In the 20th century infrastructure became much cheaper and easier to build so the average lot tended to facilitate cheap and efficient house construction. Of course you can cut your infrastructure costs in other ways, like builidng narrow streets, or not building sidewalks as in the case of many ranch house neighborhoods, but at any given width narrow lots yeild more units per foot of infrastructure than do equivalently sized square lots.

ReplyDelete